Mouse study finds impaired cell development

Intermittent fasting could be unsafe for teenagers

“Intermittent fasting is known to have benefits, including boosting metabolism and helping with weight loss and heart disease. But until now, its potential side effects weren’t well understood,” says Alexander Bartelt, the Else Kröner Fresenius Professor and Chair of Translational Nutritional Medicine at TUM. In a recently published study, the team shows that intermittent fasting during adolescence could have long-term negative effects on metabolism.

Fasting improves metabolism in older mice, but not in the young

The researchers studied three groups of mice: adolescent, adult, and older animals. The mice remained without food for one day and were fed normally on two days. After ten weeks, insulin sensitivity improved in both the adult and older mice, meaning that their metabolism responded better to insulin produced by the pancreas. This is key to regulating blood sugar levels and preventing conditions like type 2 diabetes.

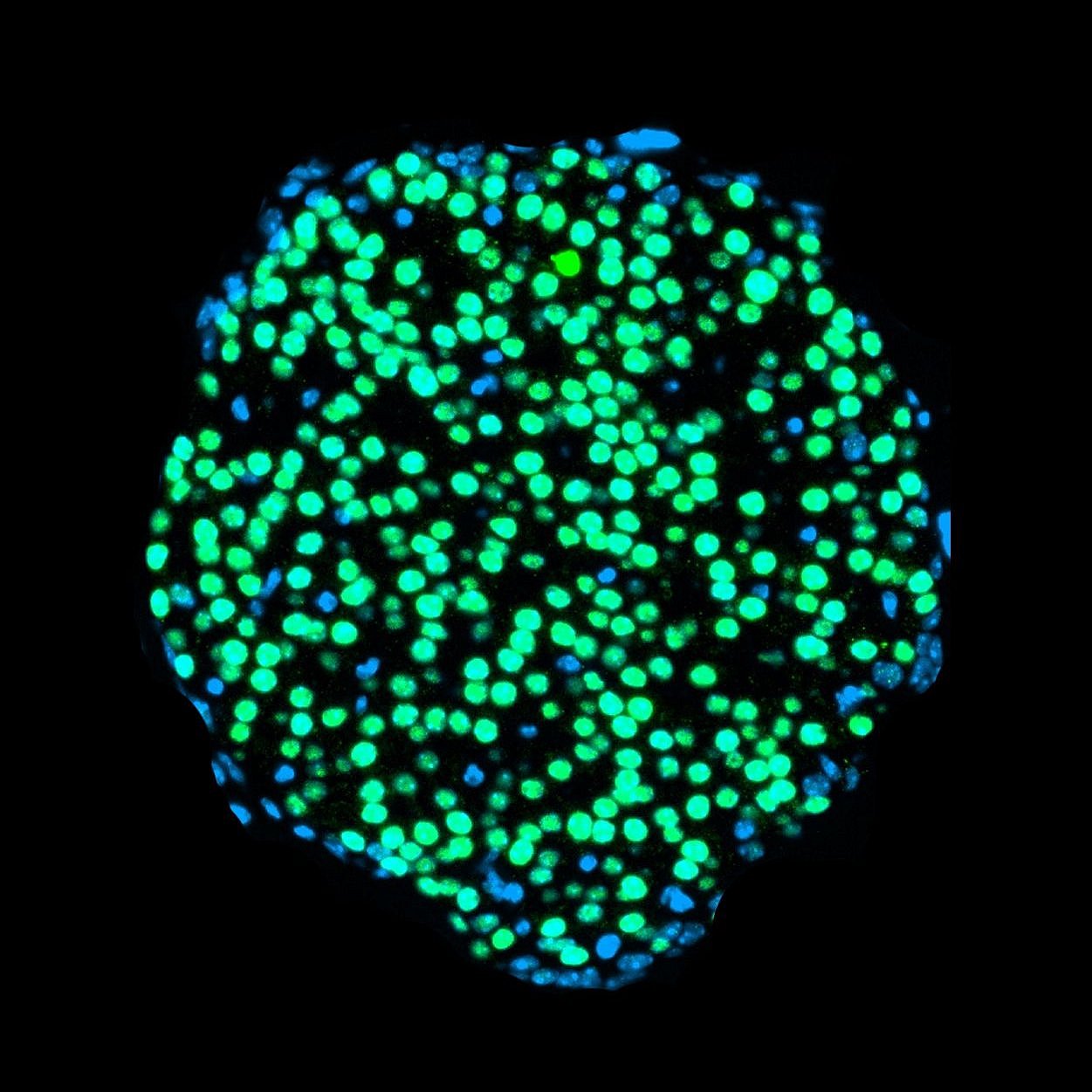

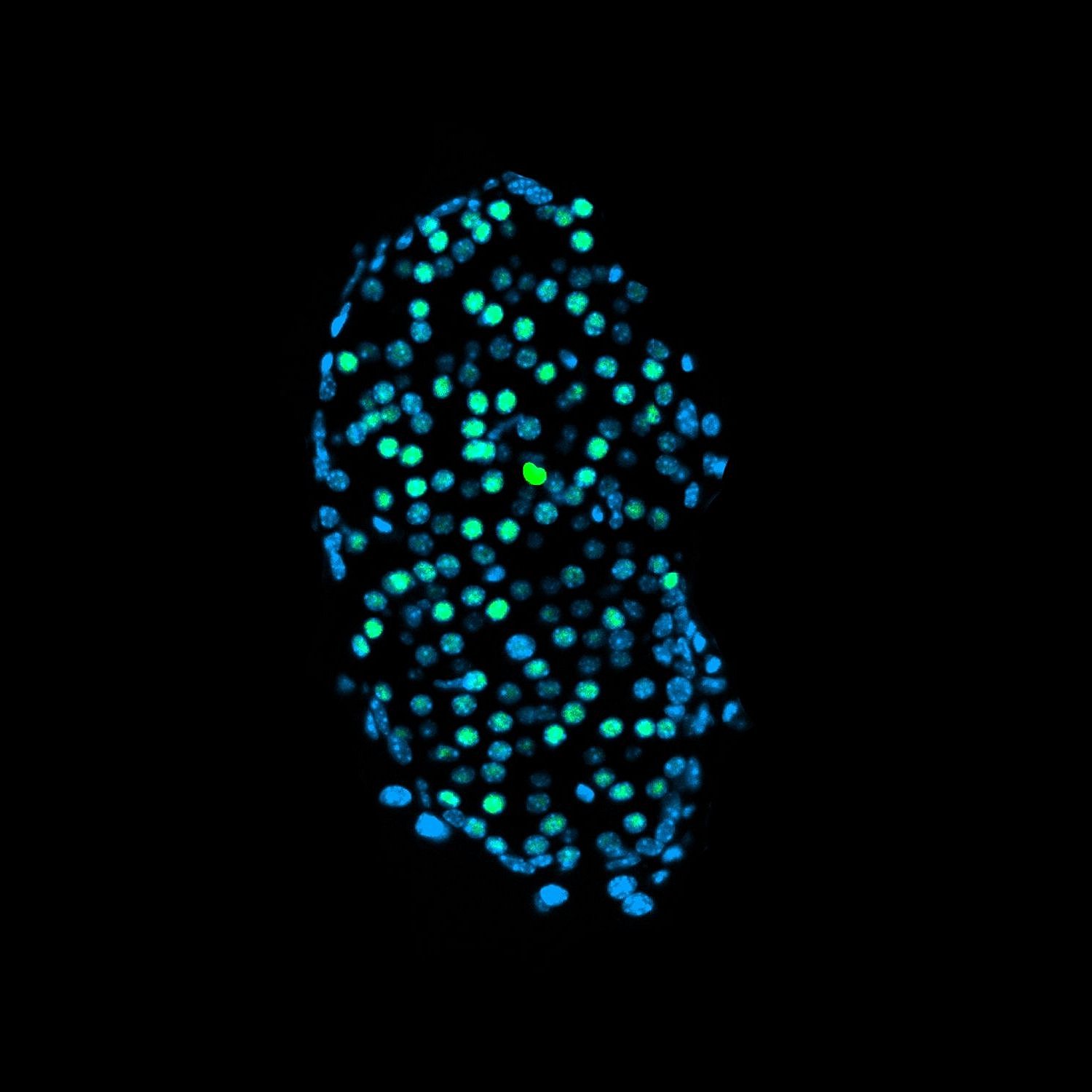

However, the adolescent mice showed a troubling decline in their beta cell function, the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas. Insufficient insulin production is linked to diabetes and disrupted metabolism. “Intermittent fasting is usually thought to benefit beta cells, so we were surprised to find that young mice produced less insulin after the extended fasting,” explains Leonardo Matta from Helmholtz Munich, one of the study’s lead authors.

Defective beta cells resemble those of type 1 diabetes patients

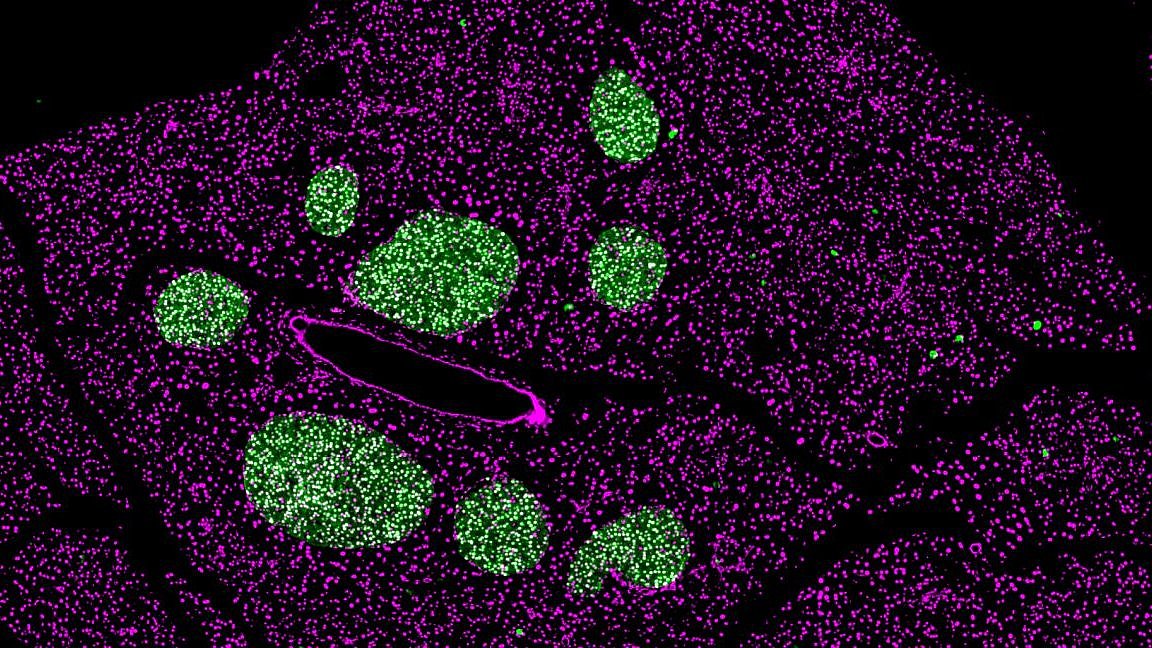

The researchers used the latest single-cell sequencing to uncover the cause of the beta cell impairment. By examining the blueprint of the pancreas, the team found that the beta cells in the younger mice failed to mature properly. “At some point, the cells in the adolescent mice stopped developing and produced less insulin,” says Peter Weber from Helmholtz Munich, also a lead author. Older mice, whose beta cells were already mature before the fasting began, remained unaffected.

The team compared their mouse findings to data from human tissues. They found that patients with type 1 diabetes, where beta cells are destroyed by an autoimmune response, showed similar signs of impaired cell maturation. This suggests that the findings from the mouse study could also be relevant to humans.

“Our study confirms that intermittent fasting is beneficial for adults, but it might come with risks for children and teenagers,” says Stephan Herzig, a professor at TUM and director of the Institute for Diabetes and Cancer at Helmholtz Munich. “The next step is digging deeper into the molecular mechanisms underlying these observations. If we better understand how to promote healthy beta cell development, it will open new avenues for treating diabetes by restoring insulin production.”

Matta, L., Weber, P., Erener, S. et al., Chronic intermittent fasting impairs β cell maturation and function in adolescent mice, Cell Reports (2025). DOI: doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2024.115225.

- Alexander Bartelt is Professor for Translational Nutritional Medicine and a member at the TUM School of Life Sciences.

- Stephan Herzig is a member at the TUM School of Medicine and Health and Director of the Institute for Diabetes and Cancer at Helmholtz Munich.

- Presentation video Prof. Alexander Bartelt.

Contacts to this article:

Prof. Dr. Alexander Bartelt

Technical University of Munich

Chair of Translational Nutritional Medicine

alexander.bartelt@tum.de

Prof. Dr. Stephan Herzig

stephan.herzig@helmholtz-muenchen.de

![[Translate to en:] TUM-Präsident Prof. Thomas F. Hofmann (links) und Stiftungsratsvorsitzender Dr. Dieter Schenk, Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung. [Translate to en:] TUM-Präsident Prof. Thomas F. Hofmann (links) und Stiftungsratsvorsitzender Dr. Dieter Schenk, Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung.](/fileadmin/_processed_/2/c/csm_220602_Foerderverlaengerung_EKFZ_88251d6d02.jpg)